Reading (& Copying) to Write

One of a series of bi-monthly posts for The MFA Project, a resource on the web for writers seeking a minimal-cost writing education.

Great fiction writers, it can be argued, are made out of good readers. And readers of everything: poetry, novels, nonfiction, magazine articles, and, if you’re like Sherman Alexie, the backs of cereal boxes. Just about everything can be fodder for the creative process, and every serious writer knows this, seeking out that special material to throw in the reptilian story processor of the mind for future deployment in the form of a short story, a poem, a novel of his or her own.

Every time we read a book, the flow, the cadences, the rhythms of sentences implant themselves in the brain. Later, and scarcely with our awareness, they eventually get shaken up, scrambled, and tossed back out, only this time as unique and fully formed expressions we’ve created ourselves. After about a week of reading a lot of books I always scratch my head in amazement when I find myself saying things in conversation, for example, that I never would have thought it in me to say. Eloquence rarely comes easily for most of us, except by spending time with words, bathing in them; and, whether you’re a poet or not (and especially if you’re a poet), putting them in your mouth and tasting them, observing their texture, noting their umpteen different shades of meaning.

In case you think that’s a little overkill, in a recent interview, renowned novelist David Mitchell expressed in the nerdiest manner possible how much he loved the language. “The best part, the part you begin with, is the sentence. Say you’re working on a sentence,” he said. “And you’ve got these ideas. Use subject, verb, object. Then, let’s make it a little Yoda-like; rearrange it a little. Someone described my character Hugo Lamb as an ‘Oxbridge Huckster.’ Lovely! Never seen those two words together, so let’s combine those. But let’s not end there, let’s have a comma – and tack on an adverb at the end. Badaboom, ch-ch-boom! It’s just GREAT.” The geekery of this comment drew laughter from his audience at the Wheeler Centre. But if you dig down, past Mitchell’s memorable characters and his innovative storytelling, it’s his enthusiasm and energy for bringing his language alive on the page that makes his writing so sublime, and why his novels have drawn such an audience.

So how do we cultivate that same Mitchell-esque passion in hopes that his brand of genius will eventually osmose into our own brains?

Francine Prose, in her book Reading Like a Writer, offers this bit of wisdom on reading novels:

With so much reading ahead of you, the temptation might be to speed up. But in fact it’s essential to slow down and read every word. Because one important thing that can be learned by reading slowly is the seemingly obvious but oddly under-appreciated fact that language is the medium we use in much the same way a composer uses notes, the way a painter uses paint…it’s surprising how easily we lose sight of the fact that words are the raw material out of which literature is crafted.

Every page was once a blank page, just as every word that appears on it now was not always there, but instead reflects the final result of countless large and small deliberations. All the elements of good writing depend on the writer’s skill in choosing one word instead of another. And what grabs and keeps our interest has everything to do with those choices.

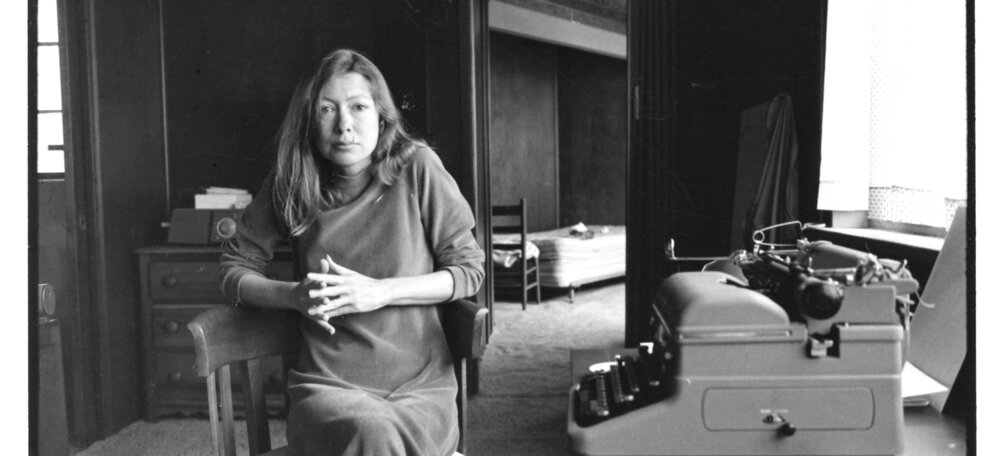

Having established that those choices are important, how do we learn from them? My own solution is copywork. Austin Kleon, in his fun little book Steal Like an Artist, encourages every writer to emulate – that is, to copy – their favorite writers. Joan Didion said that she learned to write by repeatedly copying The Great Gatsby on her typewriter, which is what we would call her “mentor text,” or work that a writer admires and learns from by taking it apart, spending time with it, and examining how it works at every level.

And what better way to do all these things with a work you admire than by copying it down? The practice has a long and almost sacred history among writers, described in this great article about the great learning afforded by copywork. And I can attest as a poet to having learned much of what I know about the craft from copying the poems of others (lately, as it happens, my material has been the hypnotic and gorgeous poems of Bruce Bond). I feared once that the voices of others would prevent me from developing my own, but have found that trying on other voices has only served to strengthen it by honing the skills that bring that voice to life.

How do you read for language? And do you have mentor texts that you return to again and again in your education as a writer? Has copywork been beneficial to your learning process? We would love to hear from you. -- Hannah

Joan Didion and her typewriter, March 31, 1972

Joan Didion and her typewriter, March 31, 1972